Anniversary of an Icon

Frank Lloyd Wright is a national hero here in the US. Everyone knows him, kids learn in school about his work, so it came as no surprise that the exhibition opening last week drew a massive crowd.

The architect was born 150 years ago in 1867. The anniversary has inspired many events and special exhibits all around the country to celebrate his work and legacy.

Here I want to share a few things that struck me wandering through the exhibition at the MoMA in New York:

Showmaster Wright

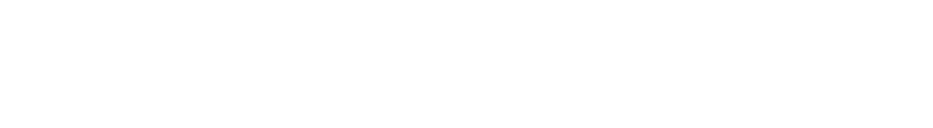

Wright was very much aware of the potential of drawings and models to build his reputation in the public and as a means to convince clients of his designs. As a conequence his scholars at Taliesin (today you would call them unpaid interns) spent hours building the most elaborate and detailed models which after each consultation with the client had to be adapted to the changes in the design.

The renderings and plans are artworks in their own right and they had their fair share in consolidating his status as a legend. In 1938 he was the first architect to be featured on the Times magazine cover and essentially became the first star architect.

However it is to say Wright not only became a darling of the press for his outstanding work, but also for his scandalous love life. T.C. Boyle’s novel The Women will tell you more about that.

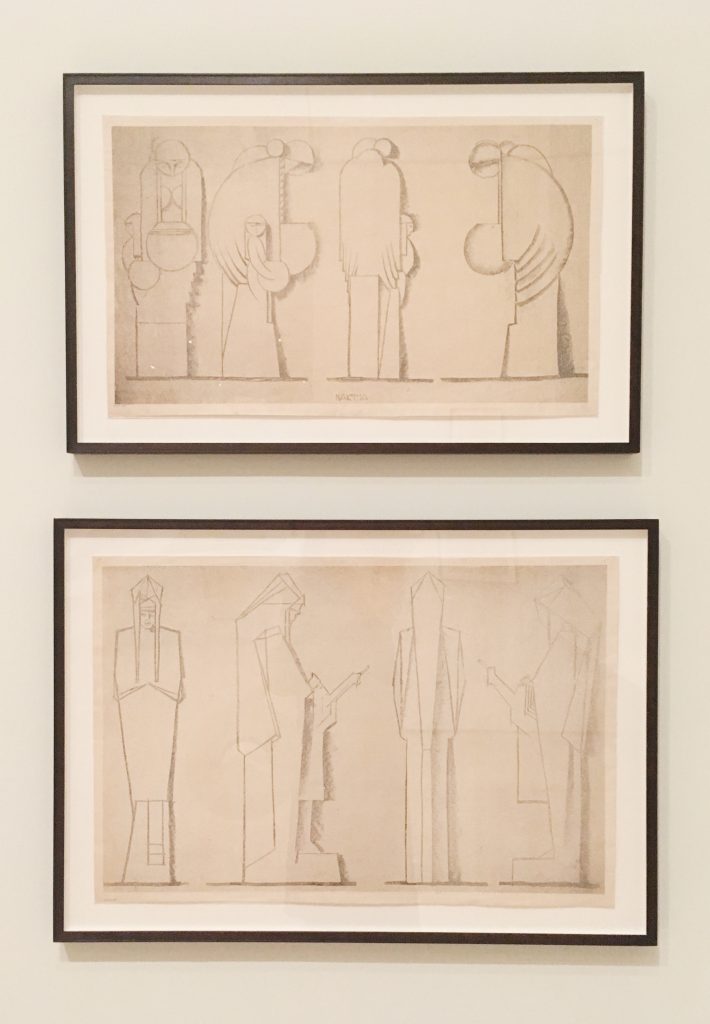

In Search for a True American Imagery

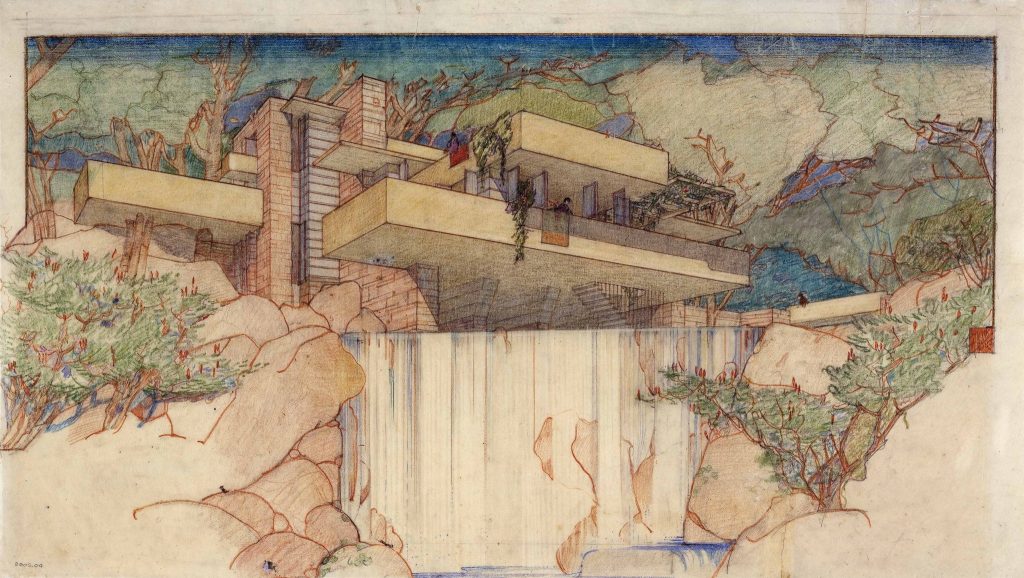

In an attempt of rooting their work in an inheritently American culture that did not rely on European precedent many architects of the time became interested in vernacular art of Native Americans and pre-Columbian cultures.

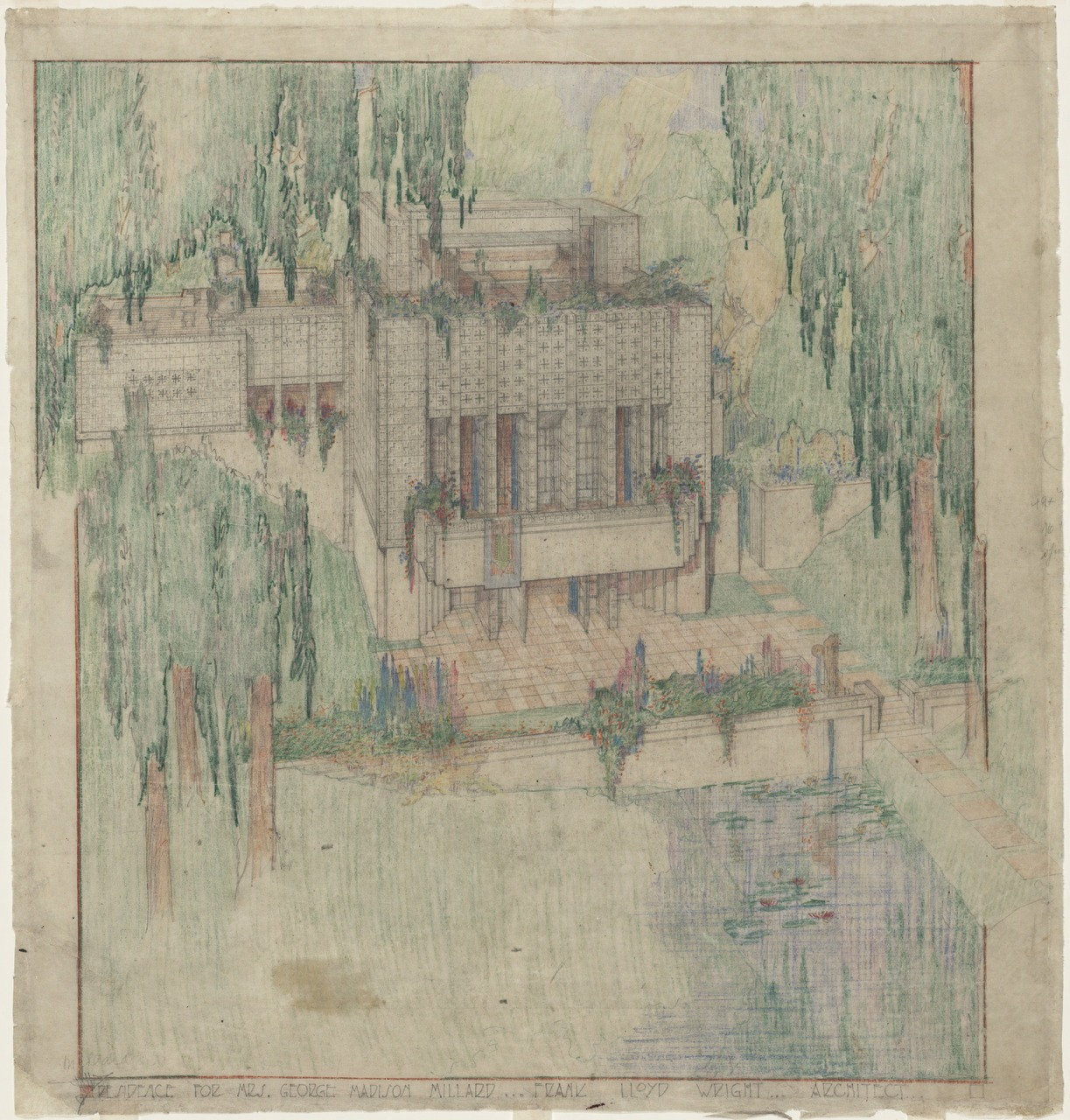

Wright developed the above pictured “textile-block”: concrete blocks stamped by hand with pre-Columbian patterns which he stacked to massive walls woven together by steel rods. The material was very cheap but achieved the intended monochromatic, monumental qulity recalling ancient Mayan ruins. Some of the blocks were perforated as to let natural light in.

See the astonishingly beautiful result for yourself here – one of the houses was recently on sale (asking price $4.5 Mio.).

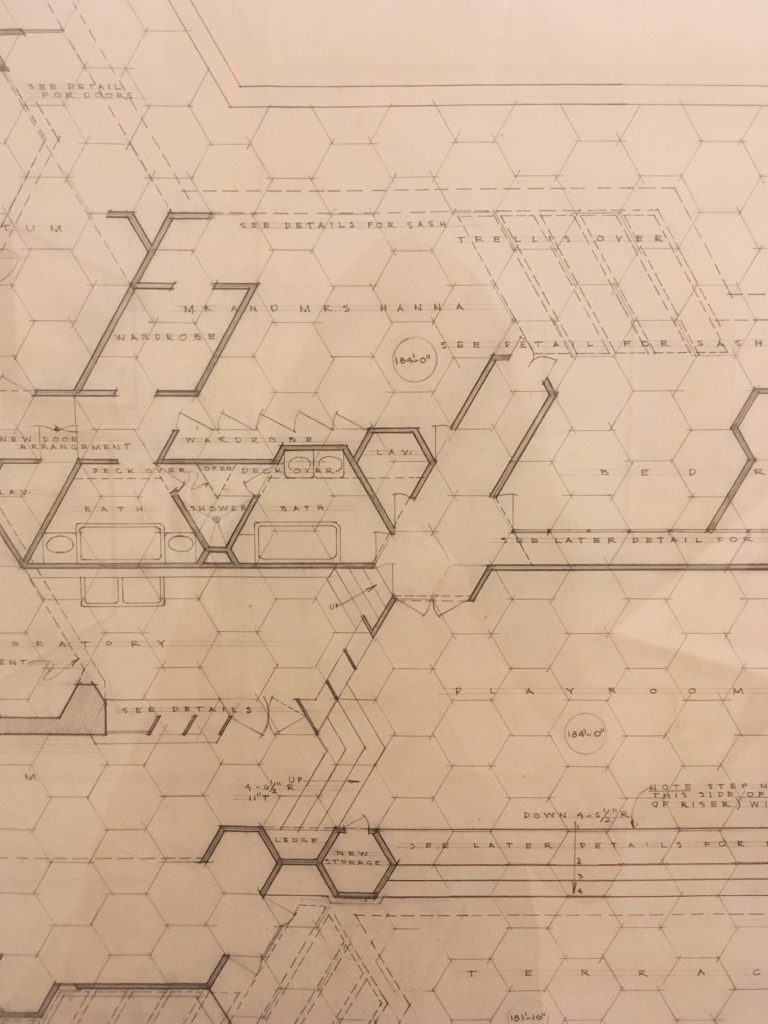

Alternatives to the Grid

I was fascinated by his experiments with alternatives to the rectancular grid as a base for his designs. Wright believed that the hexagon was more natural than a square or a right angle so he found this form particularly appropriate for dramatic landscapes with rugged terrain.

A Starchitect House on a Budget

One tends to think of Wright as a designer of uniquely luxurious mansions, but he also designed “catalogue houses” affordable to middle-class Americans and developed interesting methodes of delivering these buildings.

His first project relied on industrial production of building components that were distributed by mail-order upon which licensed constructors would ensure a professional installation.

A later project embraced more of a DIY approach: The product was essentially an instruction to enable individuals to build their own houses using self-cast concrete blocks.

If you’re inclined to hear about Wright’s very first small house for a middle-class family I urge you to listen to this awesome podcast.

For now let me leave you with this gem: The living room of Fallingwater.

Photo credits:

All photos are mine, except for:

– Fallingwater rendering: The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York) (https://www.moma.org/calendar/events/3031?locale=en)

– Millard House rendering: The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York) (https://www.moma.org/collection/works/282)

– Fallingwater Interior: www.fallingwater.org